Linear least squares computations offer a unified approach to solving diverse problems, from predicting future costs to estimating trailer parameters, as detailed in recent publications.

Numerous tutorials and resources, including those utilizing Python and MATLAB, demonstrate the least squares method’s practical application in various fields of study.

The SIAM Journal on Numerical Analysis highlights advancements in Galerkin methods, while research explores regularization techniques like bounded perturbation regularization for improved estimation.

Overview of the Least Squares Method

The Least Squares Method is a fundamental technique for finding the best-fitting line or curve to a given set of data points. It minimizes the sum of the squares of the residuals – the differences between observed and predicted values. This approach is widely used in linear least squares computations, offering a robust solution when exact fits are unattainable.

Tutorials demonstrate its implementation, calculating slope and intercept to define the optimal line. This method isn’t limited to simple linear regression; it extends to more complex models, providing a versatile tool for data analysis and prediction. The method’s strength lies in its statistical properties, offering estimates with minimal variance.

Applications span cost estimation, trailer parameter determination, and even solving partial differential equations, showcasing its broad applicability and importance in various scientific and engineering disciplines. It’s a cornerstone of modern data science.

Historical Context and Development

The origins of the Least Squares Method trace back to the work of Carl Friedrich Gauss and Adrien-Marie Legendre in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, initially developed for astronomical calculations and error minimization. Their contributions laid the groundwork for modern linear least squares computations.

Over time, the method evolved with advancements in mathematics and statistics, becoming a central technique in regression analysis. The 20th century saw its application expand into diverse fields like econometrics and engineering, fueled by the increasing availability of computational power.

Publications in journals like the SIAM Journal on Numerical Analysis demonstrate ongoing refinement and adaptation of the method, including the development of iterative techniques and regularization methods to address challenges in complex datasets. Today, it remains a cornerstone of data modeling.

Mathematical Foundations

Linear least squares computations rely on a linear regression model, cost function minimization, and the application of normal equations to derive optimal solutions.

Linear Regression Model

The linear regression model forms the bedrock of least squares computations, representing relationships between variables with a linear equation. This model assumes a linear association between an independent variable (or variables) and a dependent variable, aiming to find the best-fitting line or hyperplane.

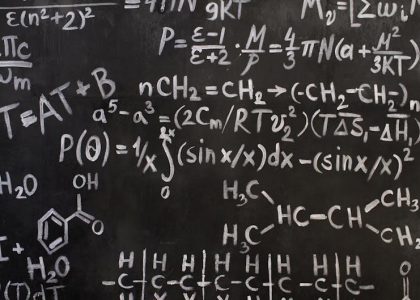

Formally, it’s expressed as y = Xβ + ε, where ‘y’ represents the observed dependent variable, ‘X’ is the design matrix containing independent variable values, ‘β’ denotes the unknown parameters (coefficients) to be estimated, and ‘ε’ signifies the error term, capturing unexplained variance.

The core principle involves minimizing the sum of squared differences between observed and predicted values, leading to unbiased estimates of the model parameters. This foundational model underpins numerous applications, including cost estimation and trailer parameter analysis, as highlighted in recent research.

Cost Function and Minimization

The cost function, central to least squares computations, quantifies the discrepancy between predicted and actual values. Typically, it’s defined as the sum of squared residuals – the squared differences between observed data points and values predicted by the linear model. Minimizing this cost function is the primary objective.

Mathematically, the cost function is expressed as J(β) = ||y ー Xβ||2, where ‘y’ is the observed vector, ‘X’ the design matrix, and ‘β’ the parameter vector. Minimization is achieved by finding the ‘β’ that yields the lowest possible value for J(β).

This minimization process, crucial for accurate cost estimation and parameter prediction, often involves calculus techniques like setting the derivative of J(β) to zero, leading to the normal equations and ultimately, the optimal parameter estimates.

Normal Equations and Solution

The normal equations arise from minimizing the cost function in linear least squares. Derived by setting the gradient of the sum of squared errors to zero, they provide a system of linear equations that, when solved, yield the optimal parameter estimates.

Specifically, the normal equations are represented as (XTX)β = XTy, where X is the design matrix, y the observation vector, and β the parameter vector we aim to determine. Solving for β involves inverting the matrix (XTX).

The solution, β̂ = (XTX)-1XTy, represents the least-squares estimator. However, if (XTX) is singular, alternative methods like the pseudoinverse or regularization techniques are employed to obtain a stable solution, ensuring accurate parameter estimation.

Computational Aspects

Linear least squares computations benefit from direct methods, iterative approaches like conjugate gradient, QR decomposition, and the powerful singular value decomposition (SVD) techniques.

Direct Methods for Solving Normal Equations

Direct methods offer a straightforward approach to solving the normal equations arising in linear least squares computations. These methods, typically involving matrix decomposition, provide a definitive solution in a finite number of steps, unlike iterative techniques.

Gaussian elimination, a fundamental technique, can be applied directly to the normal equations (ATAx = ATb) to determine the coefficient vector ‘x’. However, directly solving the normal equations can be numerically unstable, particularly when the matrix A is ill-conditioned.

Cholesky decomposition, applicable when ATA is symmetric and positive definite, offers a more stable alternative. LU decomposition with pivoting can also enhance stability. These decompositions transform the normal equations into a simpler form, facilitating efficient solution finding.

Despite their stability advantages, direct methods can be computationally expensive for large-scale problems, demanding significant memory and processing power.

Iterative Methods (e.g., Conjugate Gradient)

Iterative methods provide an alternative to direct methods for solving linear least squares computations, particularly beneficial for large-scale problems where direct approaches become computationally prohibitive. These methods refine an initial guess through successive iterations, converging towards the optimal solution.

The Conjugate Gradient (CG) method is a prominent example, especially effective for symmetric positive-definite normal equations. CG minimizes the error along conjugate directions, ensuring faster convergence than simpler iterative schemes.

Other iterative techniques include Generalized Minimal Residual (GMRES) and BiConjugate Gradient Stabilized (BiCGSTAB), suited for non-symmetric systems. These methods require less memory than direct solvers, making them ideal for high-dimensional datasets.

However, iterative methods don’t guarantee a solution in a fixed number of steps and convergence depends on factors like preconditioning and the system’s properties.

QR Decomposition for Least Squares

QR decomposition offers a numerically stable and efficient approach to solving linear least squares computations. This method decomposes the original matrix A into an orthogonal matrix Q and an upper triangular matrix R, represented as A = QR.

By transforming the problem into this form, the least squares solution can be obtained by solving a system of triangular equations, which is computationally simpler and more stable than directly solving the normal equations (ATA x = ATb).

The orthogonality of Q ensures that numerical errors are minimized during the decomposition process, leading to a more accurate solution. This technique is particularly valuable when dealing with ill-conditioned matrices.

Software packages like NumPy and SciPy in Python, and MATLAB, readily provide functions for performing QR decomposition, simplifying its implementation in practical applications.

Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) and its Application

Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) is a powerful technique applicable to linear least squares computations, providing insights beyond just finding a solution. SVD decomposes a matrix A into three matrices: U, Σ, and VT, where U and V are orthogonal, and Σ contains singular values.

In the context of least squares, SVD allows for determining the rank of the matrix A, identifying multicollinearity, and computing the minimum norm solution. The singular values in Σ reveal the importance of each dimension in the data.

Truncating smaller singular values effectively implements regularization, enhancing the stability and generalization ability of the solution, similar to Ridge Regression. This is particularly useful when dealing with noisy or incomplete data.

Software like Python’s NumPy and SciPy, and MATLAB, offer robust SVD implementations for efficient computation and analysis.

Regularization Techniques

Regularization techniques, like Ridge and Lasso regression, address overfitting in linear least squares computations, improving model generalization and stability through parameter control.

Bounded Perturbation Regularization (BPR) offers a novel approach to parameter selection, enhancing the robustness of the estimated solutions.

Ridge Regression (L2 Regularization)

Ridge Regression, a cornerstone of linear least squares computations, introduces an L2 penalty to the cost function, effectively shrinking coefficient magnitudes and mitigating multicollinearity issues.

This technique adds a term proportional to the sum of the squared values of the coefficients to the standard least squares objective, controlled by a tuning parameter (lambda or alpha).

Larger lambda values induce stronger shrinkage, leading to simpler models with reduced variance, albeit potentially increased bias. Conversely, smaller values approach ordinary least squares.

The regularization path visualization, a common practice, illustrates how coefficients change across different lambda values, aiding in optimal parameter selection.

Implementation in Python (scikit-learn) and MATLAB is straightforward, offering efficient computation and model evaluation capabilities for robust predictive modeling.

Lasso Regression (L1 Regularization)

Lasso Regression, another vital technique in linear least squares computations, employs L1 regularization, adding a penalty proportional to the absolute value of the coefficients to the cost function.

Unlike Ridge Regression’s L2 penalty, L1 regularization encourages sparsity in the model, driving some coefficients to exactly zero, effectively performing feature selection.

This characteristic is particularly valuable when dealing with high-dimensional datasets where many features may be irrelevant or redundant, simplifying the model and improving interpretability.

Similar to Ridge, a tuning parameter (lambda or alpha) controls the strength of the penalty, influencing the degree of sparsity and the trade-off between bias and variance.

Python’s scikit-learn and MATLAB provide tools for implementing Lasso, visualizing regularization paths, and evaluating model performance across different parameter settings.

Bounded Perturbation Regularization (BPR)

Bounded Perturbation Regularization (BPR) represents an innovative approach to parameter selection in linear least-squares estimation, addressing challenges in model stability and generalization.

This technique, detailed in recent research, introduces a novel regularization method designed to control the sensitivity of the solution to perturbations in the data, enhancing robustness.

BPR aims to find a regularization parameter that minimizes the impact of small changes in the observed data on the estimated coefficients, leading to more reliable predictions.

Unlike traditional methods, BPR focuses on bounding the perturbation of the solution, ensuring that the estimated parameters remain within a reasonable range even with noisy inputs.

The implementation and evaluation of BPR often involve computational tools and libraries, allowing for a quantitative assessment of its performance compared to other regularization techniques.

Applications of Linear Least Squares

Linear least squares finds broad application in cost estimation, trailer parameter analysis, and solving mixed-type partial differential equations, offering versatile solutions.

Cost Estimation and Prediction

Cost estimation, the process of predicting future expenses based on historical data, heavily utilizes linear least squares regression as a core methodology. This technique aims to establish a relationship between cost drivers and anticipated expenditures, providing a quantifiable basis for budgetary planning and financial forecasting.

By applying the least squares method, analysts can minimize the sum of squared differences between predicted and actual costs, resulting in a model that best fits the available data. This approach is particularly valuable in scenarios where numerous factors influence costs, and a clear, mathematically defined relationship is desired.

The accuracy of cost predictions derived from linear least squares depends on the quality and relevance of the historical data, as well as the appropriate selection of cost drivers. Effective implementation requires careful consideration of potential biases and limitations within the dataset.

Trailer Parameter Estimation

Linear model-based least squares methods provide a robust framework for accurately determining crucial trailer parameters, specifically trailer and hitch lengths. This application is vital for optimizing vehicle dynamics, ensuring safe towing operations, and improving overall transportation efficiency.

Researchers have developed closed-form linear regression solutions, leveraging the principles of least squares computations, to estimate these parameters directly from observed data. These methods offer a practical alternative to traditional measurement techniques, which can be time-consuming and prone to errors.

The accuracy of the estimated parameters relies on the quality of the input data and the precise formulation of the linear model. Careful consideration must be given to factors such as sensor noise and vehicle configuration to achieve reliable results, enhancing the safety and performance of towing systems.

Solving Partial Differential Equations (Mixed-Type)

Linear least squares methods offer a powerful numerical approach to solving complex mixed-type partial differential equations (PDEs), presenting a unified computational treatment for both elliptic and hyperbolic components. This is particularly valuable in scenarios where traditional methods struggle due to the equation’s changing characteristics.

Recent analyses demonstrate the effectiveness of least-squares techniques in achieving accurate and stable solutions for these challenging PDEs. The method involves formulating the problem in a least-squares framework, minimizing the residual error across the domain.

Publications in the SIAM Journal on Numerical Analysis detail advancements in least-squares Galerkin methods, enhancing the efficiency and precision of PDE solutions. These techniques are crucial for modeling diverse physical phenomena, offering a versatile tool for scientific computing and engineering applications.

Software and Tools

Python libraries like NumPy, SciPy, and scikit-learn, alongside MATLAB and R, provide robust tools for performing linear least squares computations efficiently.

Python Libraries (NumPy, SciPy, scikit-learn)

Python’s ecosystem offers powerful libraries for implementing linear least squares computations. NumPy provides fundamental array operations and linear algebra routines, forming the base for numerical work.

SciPy builds upon NumPy, offering specialized functions like scipy.linalg.lstsq, directly solving least squares problems with options for regularization and handling rank-deficient matrices.

Scikit-learn provides a higher-level interface with its LinearRegression class, simplifying model training and prediction, and integrating seamlessly with other machine learning tools.

These libraries facilitate efficient computation, model evaluation, and visualization, making Python a preferred choice for researchers and practitioners alike, as demonstrated in numerous tutorials.

The availability of these tools streamlines the process, allowing users to focus on problem formulation and interpretation of results rather than low-level implementation details.

MATLAB Implementation

MATLAB provides robust built-in functions for performing linear least squares computations. The backslash operator () is a fundamental tool, efficiently solving systems of linear equations, including overdetermined systems arising in least squares problems.

Functions like lsqr and pinv offer alternative approaches, particularly useful for large-scale or ill-conditioned problems, providing control over iterative solvers and pseudo-inverse calculations.

MATLAB’s environment facilitates easy visualization of results and experimentation with different regularization techniques, aiding in model validation and parameter tuning.

Its extensive documentation and readily available examples make it a popular choice for both academic research and practical applications, as evidenced by its widespread use in numerical analysis.

The integrated development environment and powerful plotting capabilities enhance the workflow for analyzing and presenting least squares solutions.

R Statistical Computing

R offers a comprehensive suite of tools for linear least squares computations, making it a favored environment for statistical analysis and modeling. The lm function is central, providing a straightforward interface for fitting linear models and performing least squares regression.

Packages like stats and lme4 extend R’s capabilities, enabling the analysis of more complex models, including mixed-effects models and generalized least squares.

R’s extensive visualization tools, such as ggplot2, facilitate the exploration of model results and the assessment of model fit.

The availability of numerous packages for regularization techniques, like ridge and lasso regression, enhances its utility in addressing overfitting and improving prediction accuracy.

R’s open-source nature and active community support contribute to its widespread adoption in both academic and industrial settings.

Advanced Topics

Advanced explorations include weighted least squares, nonlinear models, and rigorous model evaluation, enhancing predictive power and addressing complex data characteristics.

Weighted Least Squares

Weighted least squares (WLS) represent a powerful extension of the standard linear least squares method, particularly valuable when dealing with heteroscedasticity – situations where the variance of the error term isn’t constant across all observations.

Unlike ordinary least squares, which assumes equal variance, WLS assigns different weights to each data point, inversely proportional to its variance. This means observations with higher variance receive lower weights, reducing their influence on the regression line, and vice versa.

Implementing WLS requires prior knowledge or estimation of the error variances. Accurate weighting significantly improves the efficiency and reliability of parameter estimates, leading to more precise predictions and inferences. This technique is crucial in applications where measurement errors vary systematically.

Various statistical software packages, including those in Python and MATLAB, provide functionalities for performing weighted least squares regression, facilitating its application in diverse fields.

Nonlinear Least Squares (Brief Mention)

While this discussion primarily focuses on linear least squares, it’s important to acknowledge the existence of nonlinear least squares (NLS). NLS arises when the relationship between the independent and dependent variables isn’t linear, requiring iterative optimization techniques to find the best-fit parameters.

Unlike linear least squares, which has a closed-form solution, NLS relies on algorithms like the Gauss-Newton or Levenberg-Marquardt methods to minimize the sum of squared residuals. These methods involve successive approximations, converging towards the optimal parameter values.

NLS is frequently encountered in modeling complex phenomena in fields like chemistry, biology, and engineering, where linear models are inadequate. Software packages like SciPy in Python and MATLAB offer robust NLS functionalities.

However, NLS can be computationally more demanding and sensitive to initial parameter guesses compared to its linear counterpart.

Model Evaluation and Validation

Model evaluation and validation are crucial steps following the application of linear least squares. Assessing the model’s performance ensures its reliability and generalizability beyond the training data. Key metrics include the Residual Sum of Squares (RSS), R-squared, and Mean Squared Error (MSE).

Techniques like visualizing regularization paths, as highlighted in recent tutorials, help understand how coefficient changes impact model performance with varying tuning parameters. Splitting the data into training, validation, and test sets allows for unbiased evaluation.

The validation set aids in parameter tuning, while the test set provides a final assessment of the model’s predictive power on unseen data. Careful consideration of these steps is vital for building robust and trustworthy models.

Proper validation prevents overfitting and ensures the model accurately reflects the underlying relationships within the data.